During the months and years when the Western Allies prepared for the invasion of continental Europe, heavy fighting occurred in the skies. Fighter and bomber pilots hammered at German industry, and slowly but inexorably diluted the strength of the mighty Luftwaffe. Still, waging an aerial campaign over enemy-controlled territory involved losing aircraft and men. About a third of the airmen from shot down aircraft managed to jump out of their crippled planes, hoping that their parachutes had not been damaged during combat.

Luckily for them, some of the action took place over the occupied lands of Europe, where the airmen could reasonably count on help from the local anti-German resistance movement. Still, the Germans apprehended many of the flyers and took them to one of the numerous prisoner of war camps across lands occupied or annexed by Nazi Germany. Regardless of whether the airmen wanted to avoid capture or escape from captivity, they needed reliable maps to navigate their way to the safety of a resistance cell or a neutral country, and, eventually, back to Britain.

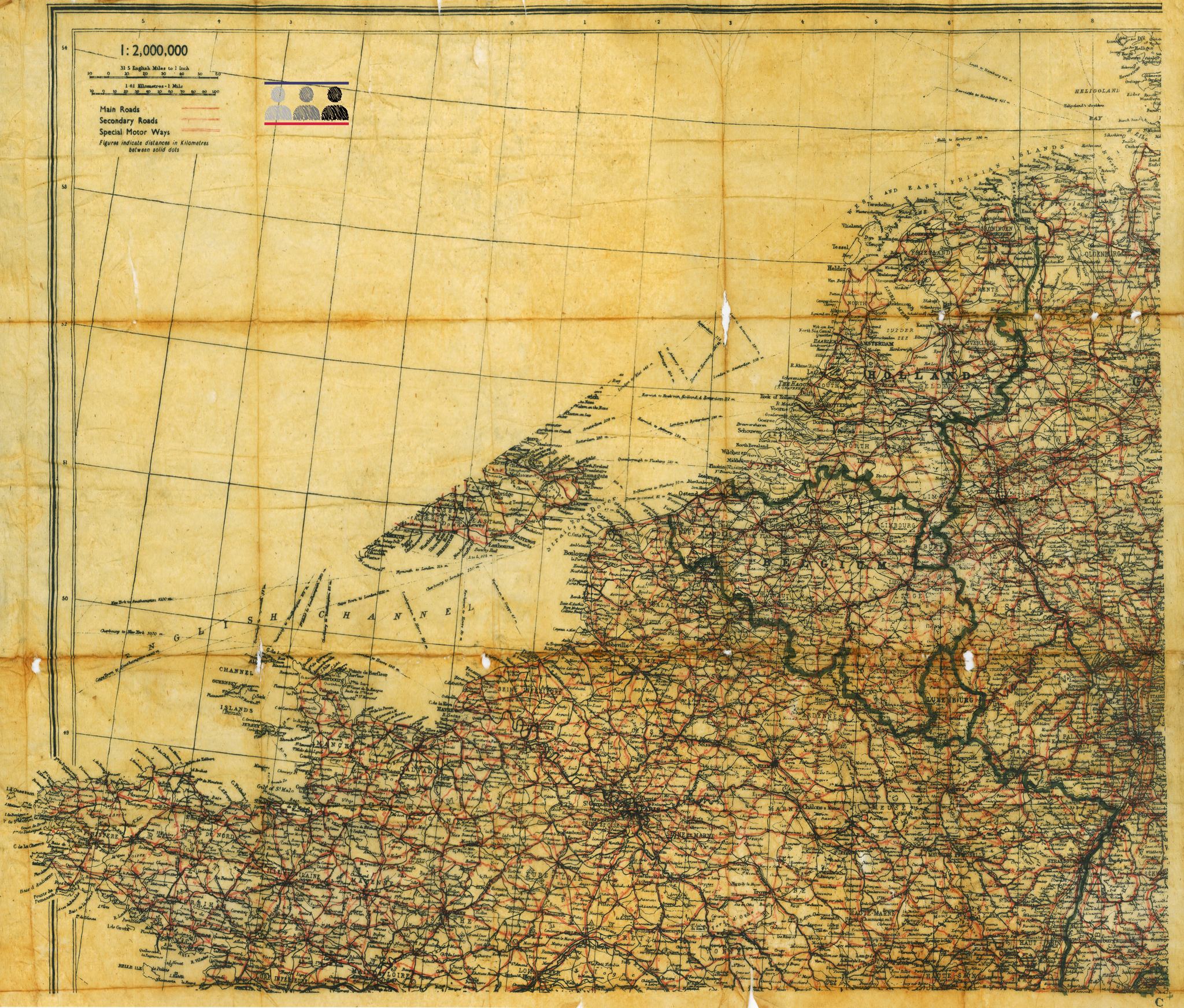

But how to provide a person with a portable, durable and, last but not least, easy-to-conceal map? The answer was found by British Intelligence (MI-9), who started printing basic maps of the relevant areas on scraps of silk, cloth or rice paper. As opposed to ordinary paper, these materials are resistant to water damage, easy to fold and, when hidden on a person, hardly detectable during a casual frisk. Soon, silk maps were issued to airmen before missions. British MI-9 and-- after the U.S. had joined the war--America’s MIS-X, developed ingenious ways to smuggle silk maps to POW camps to facilitate escape attempts.

They created various types of maps. Some showed the entire area over which an air mission took place, so that an airman, having landed by parachute, could check local signposts and place names, identify his location, and determine his next steps. Others depicted the areas surrounding the POW camps, and were essential for planning an escape attempt. Still others were more specialized, showing plans of towns or seaports that were used to hide or smuggle escaped prisoners.

One such map, printed on a rice paper, has found its way to our foundation, donated by Marek Łazarz, the Director of the P.O.W. Camps Museum in Żagań, located at the site of the famous Stalag Luft 3 in Sagan. This map shows the entire north-western coast of occupied Europe, and without any doubt had been issued to airmen taking part in the bombing campaign. The map was found in 2011 during cleaning works in one of the sectors of the former camp. Its condition is truly a testimony to the quality of the escape maps produced during the war that, even after more than 70 years in a a metal can buried in the ground, the map appears almost pristine.

Allied intelligence also produced a map showing the surroundings of Oflag 64, stretching as far as Bydgoszcz, the nearest large city. This map would have been a great addition to our collections but, unfortunately, so far, our attempts at obtaining one of them have proved futile. We also know that there is at least one preserved map that belonged to one of Oflag 64 Kriegies. But hush for now, this will be a great news in our community :)

To learn more (or perhaps all there is to learn) about the escape maps, see the comprehensive website: escape-maps.com

Among the presented maps is also the mother of the Szubin area: escape-maps.com/escape_maps/wwii_us_tissue_szubin.htm